The interconnections between climate, vegetation and soils in the development of temperate deciduous woodland

The development of temperate deciduous woodlands is heavily influenced by a complex interplay between climate, vegetation, and soils. Each of these factors not only shapes the characteristics of temperate deciduous forests but also contributes to the evolution and sustainability of these ecosystems. Below is an analysis of these interconnections, supported by scientific references.

1. Climate and Temperate Deciduous Woodlands

The climate is a key driver in determining the location and characteristics of temperate deciduous woodlands. These forests typically thrive in temperate regions, which are characterised by distinct seasonal changes, with cold winters and warm summers, and moderate annual precipitation.

Temperature and Precipitation: The climate in temperate deciduous woodlands is typically characterised by a cool to moderate temperature range, with average temperatures between 5°C to 15°C. Rainfall is evenly distributed throughout the year, with annual precipitation ranging from 750 mm to 1,500 mm. This climate supports a variety of deciduous tree species that shed their leaves in winter to conserve energy during the colder months (Whittaker, 1975).

Seasonal Variations: Seasonal changes, such as the warm, wet growing season and cold, dry winter, influence the growth cycles of trees and plants in these ecosystems. Deciduous trees are adapted to this seasonal cycle by losing leaves in the winter to minimise water loss during the dry, cold months. In contrast, coniferous trees are more suited to harsher climates with colder winters and shorter growing seasons (Körner, 2015).

Example: In Europe and North America, temperate deciduous woodlands are typically found between 30° and 50° latitude, where these climatic conditions prevail. The Eastern United States and much of Europe are prime examples of such ecosystems (Bailey, 2009).

Reference: Whittaker, R. H. (1975). Communities and Ecosystems. Macmillan.

Körner, C. (2015). Ecophysiology of High Mountain Plants. Springer.

Bailey, R. G. (2009). Ecoregions: The Ecosystem Geography of the Oceans and Continents. Springer.

2. Vegetation in Temperate Deciduous Woodlands

The vegetation of temperate deciduous woodlands is closely tied to both the climate and soil conditions. These forests are dominated by broadleaf trees, such as oak (Quercus spp.), beech (Fagus sylvatica), maple (Acer spp.), and ash (Fraxinus spp.), along with a rich understory of shrubs, herbs, and ferns.

Tree Adaptations: The dominant tree species in temperate deciduous woodlands have adapted to the seasonal climate by shedding their leaves in winter. This adaptation allows the trees to survive the cold and dry winter months by reducing water loss through transpiration. Additionally, the ability to photosynthesize during the warm months provides sufficient energy for growth and reproduction.

Species Composition: The composition of vegetation varies depending on local microclimates and soil types. In more fertile soils, larger trees like oak and beech dominate the canopy, while in poorer soils, species such as birch (Betula spp.) and ash may be more prevalent. The understory plants include species such as bluebells (Hyacinthoides non-scripta), wild garlic (Allium ursinum), and various ferns, which thrive in the dappled sunlight of the forest floor (Odum, 1971).

Example: The broadleaf forests of the eastern United States (e.g., the Appalachian Mountains) are an example of temperate deciduous woodlands where a variety of tree species and understory plants coexist under a distinct seasonal cycle (Nowacki & Abrams, 2008).

Reference: Odum, E. P. (1971). Fundamentals of Ecology. Saunders.

Nowacki, G. J., & Abrams, M. D. (2008). "The impact of climate change on temperate forests in North America." The Journal of Ecology, 96(4), 665-683.

3. Soil Characteristics and Their Role in Forest Development

Soils are a critical factor in the development of temperate deciduous woodlands. The types of soils found in these forests depend largely on the climate and vegetation, and they, in turn, influence the type of vegetation that can thrive in a given area.

Soil Fertility: Temperate deciduous woodlands typically occur on fertile, well-drained soils. These soils are often rich in organic matter due to the regular leaf fall in autumn, which decomposes and contributes to soil fertility. The decomposition of dead plant material creates humus, which improves the water retention and nutrient availability in the soil.

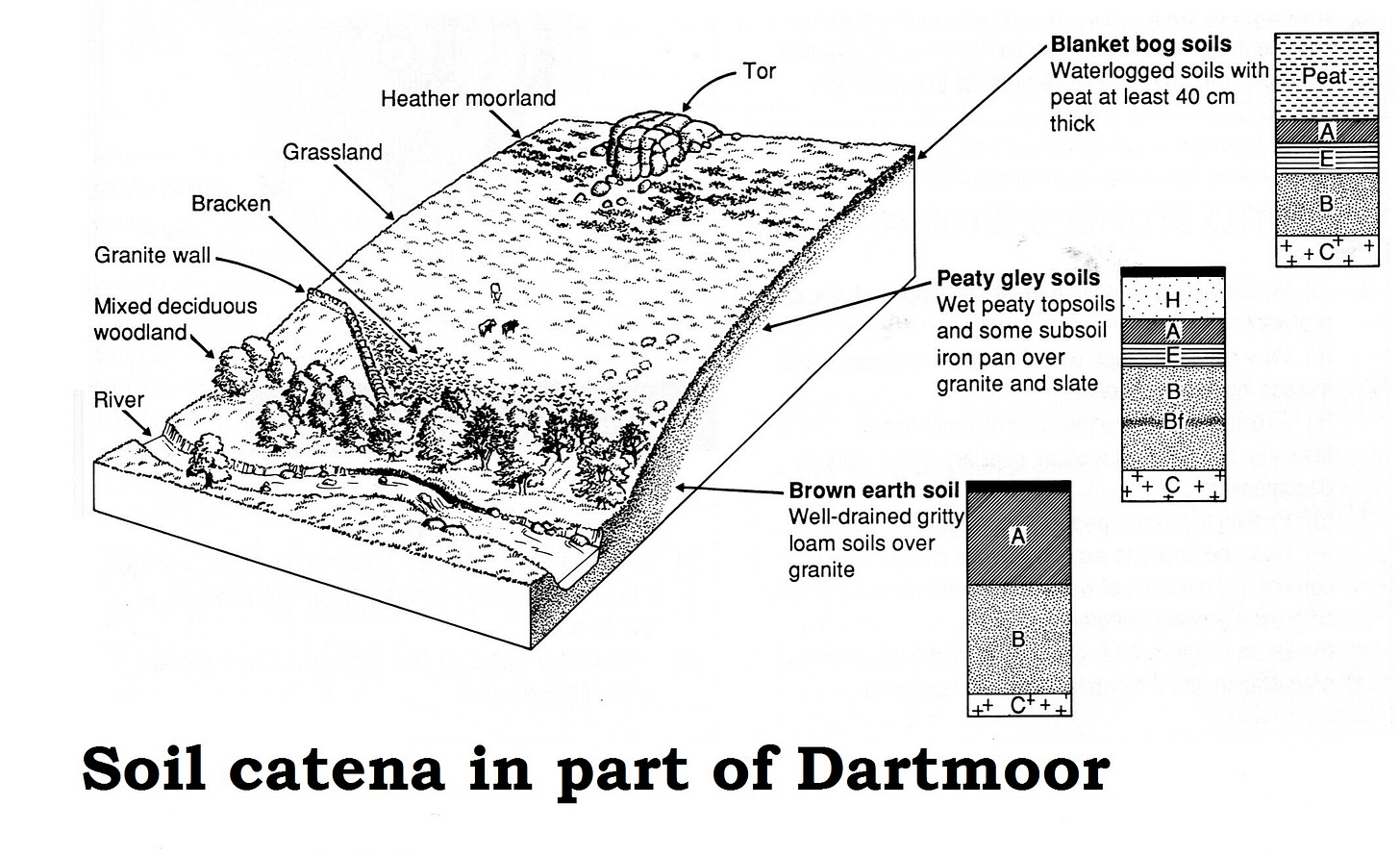

Soil Types: The soil in temperate deciduous woodlands can be classified into several types, including podzols (acidic soils often found in northern regions) and brown earths (rich, fertile soils found in temperate regions). Brown earths are commonly associated with deciduous woodlands because they support the high levels of plant growth needed for these forests (Lamb, 1994). The soil pH, texture, and nutrient levels determine which species of trees and plants can grow and thrive in a particular area.

Soil-Plant Feedbacks: There is a feedback loop between vegetation and soil. As vegetation grows and decomposes, it influences the soil’s chemical composition, particularly its nutrient levels and pH. In turn, the soil quality impacts plant growth. For example, the decaying leaves of oak trees contribute to the acidity of the soil, which may limit the growth of certain plants but allow others to thrive (Binkley et al., 2003).

Example: In temperate deciduous forests of Europe, beech and oak are dominant species on nutrient-rich soils, whereas on less fertile, acidic soils, species like Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) or birch may prevail (Binkley et al., 2003).

Reference: Lamb, H. F. (1994). Vegetation and Environment. Cambridge University Press.

Binkley, D., & Fisher, R. F. (2003). Ecology of Forests. Springer.

4. Interconnections Between Climate, Vegetation, and Soils

The development of temperate deciduous woodlands is the result of complex interconnections between climate, vegetation, and soils:

Vegetation and Climate: The seasonal climate (cold winters and warm summers) drives the selection of deciduous trees, which adapt by shedding leaves to conserve water during the winter months. This adaptation also affects the soil's organic content as fallen leaves decompose and enrich the soil.

Soils and Vegetation: Soil fertility, pH, and texture directly affect the types of plants that can establish themselves. In turn, the vegetation affects the soil, influencing factors like moisture retention, nutrient cycling, and organic matter decomposition. For instance, deep-rooted deciduous trees can influence the soil structure by preventing erosion and creating space for understory plants.

Climate and Soils: The seasonal climate determines the rate of organic matter decomposition and soil nutrient cycling. In colder climates, decomposition slows down in the winter, leading to the accumulation of organic matter, while in warmer climates, faster decomposition rates lead to less organic accumulation.

Conclusion

The development of temperate deciduous woodlands is a result of the dynamic interactions between climate, vegetation, and soils. The climate provides the conditions that favour deciduous trees, which are adapted to the seasonal temperature fluctuations and precipitation. These trees, in turn, influence the soil through the accumulation of organic matter, which affects soil fertility and structure. The soil conditions, such as pH and nutrient levels, ultimately determine which species of plants can thrive in these ecosystems. The interconnections between these factors make temperate deciduous woodlands highly adaptive but also highly sensitive to changes in climate and land use.

References

Whittaker, R. H. (1975). Communities and Ecosystems. Macmillan.

Körner, C. (2015). Ecophysiology of High Mountain Plants. Springer.

Bailey, R. G. (2009). Ecoregions: The Ecosystem Geography of the Oceans and Continents. Springer.

Odum, E. P. (1971). Fundamentals of Ecology. Saunders.

Nowacki, G. J., & Abrams, M. D. (2008). "The impact of climate change on temperate forests in North America." The Journal of Ecology, 96(4), 665-683.

Lamb, H. F. (1994). Vegetation and Environment. Cambridge University Press.

Binkley, D., & Fisher, R. F. (2003). Ecology of Forests. Springer.

FEEL FREE TO BUY ME A COFFEE IF YOU LIKE MY FREE RESOURCES

or one of my inexpensive books at

Amazon.co.uk: Ritchie Cunningham: books, biography, latest update